Compositional Style and Meditation on

Rudolf Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom:

Some tips from the O’Neils

By Mark Riccio

George and Gisela O’Neil, two leaders in American Anthroposophy, passed away in 1988, but even in death they are still ahead of their time. It is not so much what they said, but how they studied, meditated, and composed/wrote.[i] They were best known for their many articles in the Anthroposophical Newsletter and the book, The Human Life.[ii] The duo dedicated their lives to deciphering, studying, and teaching Steiner’s compositional style and meditation technique on the Philosophy of Freedom[iii] called “pure thinking” or organic-living thinking. The future of Anthroposophy will depend on whether its members can study together in a new way, since the old way is simply too intellectualized. This short essay is a call to change your thinking about how you read a Steiner book and what type of activities you do during valuable anthroposophical study time. Here is an overview of their method.

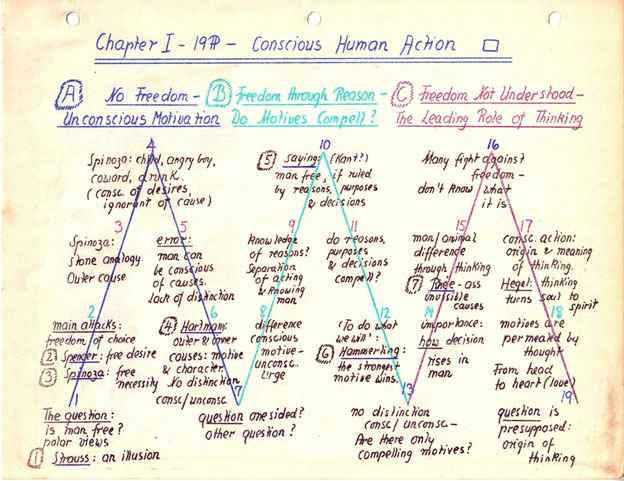

George’s Diagram of the Philosophy of Freedom

Style, Whole to Parts, Symmetry, and Imitation:

George and Gisela followed Steiner’s dictate that one should “enter into the thought-style” of his Philosophy of Freedom and as a result they mapped out the thought-patterns in the whole book. In order to do this, the researcher needs to know the content to the highest degree and from there look at the style or form i.e., how the author put together their paragraphs, sentences and so on. It is a profound remark from Rudolf Steiner that style should be the path, not simply the content or as Steiner put it one should become aware of “how one thought follows the other.” Once George and Gisela finished mapping a book and meditating its chapters over and over again, they printed and handed it out to their students. They produced amazing research notes on Theosophy, Occult Science, and Knowledge of Higher Worlds covering both content and style.

George and Gisela always approached a Steiner book from the whole-to-the-parts. For example, George compared the paragraphs of Chapter I, Conscious Human Action of the Philosophy of Freedom. Looking at his paragraph synopses, he noticed a pattern (see bottom of the article for the list of synopses). Every seventh paragraph rephrased the freedom question! Thus, paragraphs, 1, 7, 13, and 19 serve as thematic breaks in Chapter I. Coincidence? The whole-to-the-parts approach is a first step in uncovering patterns in an author’s thought-style.

George and Gisela also took notice of the fact that the midpoint, the middle paragraph in a chapter of the Philosophy of Freedom is of pivotal importance. In Chapter I, the midpoint is the tenth paragraph where free will is defined as the carrying out of rational decisions (Kant). It is the first time in the chapter where freedom is defined positively, however according to Steiner incorrectly. It is a kind of turning inside out of the thought process from negative to positive! Next time you read a Steiner text, see if you can find where the midpoint is and whether it signals a change in Steiner’s thought-process.

George and Gisela in their pursuit of Steiner’s method and style of writing found that symmetry (also called polarity) was evident. Steiner often describes the ‘outer aspect’ of his topic first and switches to an inner perspective. For example, in Chapter I of the Philosophy of Freedom, Steiner has a series of symmetrical paragraphs that stand in polarity:

Paragraph 1 and Paragraph 7 are about the freedom question and additional questions

Paragraph 2 and Paragraph 6 are about external compulsion (Spinoza) vs. internal compulsion (Hartmann)

Paragraph 3 and Paragraph 5 are about Spinoza’s model and Spinoza’s error

Paragraph 4 has Spinoza’s definition of freedom – stands alone without symmetry.

Keep your eyes open when you read your favorite Steiner text. You just may detect such subtle movements. You may even consider bringing these compositional relationships into your own writing. The Human Life was the first English book in which Steiner’s special method of writing was consciously used by George and Gisela. By imitating Steiner’s style of writing, one may get closer to a “spiritual style” of composing found, by the way, in other classic spiritual authors as well. Conscious imitation of Steiner’s morphological thinking is another step toward actively employing Steiner’s universal organic style of writing.

George’s approach sheds light on Steiner’s work such as the form of the Calendar of the Soul, the Waldorf Curriculum themes, the Our Father Prayer, and even the architecture of the Goetheanum. Most importantly, it invigorates group study.

Grounding the New Thinking:

When George and Gisela first presented their new thinking discoveries in the United States, they were either totally misunderstood, or simply laughed at. However, in 1993 the energy around the new thinking changed as Germany embraced George’s findings, in particular Freies Geistesleben Press in Stuttgart, when it published Florin Lowndes’ Human Life, The Enlivening of the Chakra of the Heart[iv] and Das Erwecken des Herzdenkens - all of which contain George’s thoughtful approach to Steiner’s anthroposophy. Spiritually speaking, it is a significant event that Steiner’s own method became officially recognized and grounded in Germany. There is no turning back as more and more people have been able to find what they were looking for in Steiner’s work: not only a new content, but a new style of thinking!

In my experience, a new species of Steiner reader has finally arrived that grasps this new thinking with ease; and the generation who rejected what is obvious to careful eyes and ears are gradually exiting, thereby opening Anthroposophy to its own method! Remember this organic thinking in The Philosophy of Freedom built Waldorf, The Goetheanum, and has much more work to do. One may not know all of the details of this new thinking today, but within a few months one can the learn the basics and start incorporating it into study and life.

Many who practice George’s work are shocked and puzzled that his research and approach are not central to branch life and branch concerns. Can you recall a branch group that is seeking the answer to the question: How does one enter into the thought-style in the Philosophy of Freedom? (Certainly not the branch near my house) The ubiquitous reading around in an anthroposophical circle, or worse Goethean kaffeeklatsch, was never a task designated by Steiner. The new thinking has been grounded and is available to all who are interested in becoming one of the 48 members carrying the Michaelic thinking that Steiner’s called to service in his last address.

George O’Neil on Meditating the Philosophy of Freedom:

The meditation of the Philosophy of Freedom is one of George’s least known contributions. In his Workbook to the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity George gives terse instructions: learn the content, master the form, and connect with the being beyond the form! Luckily, in Das Erwecken des Herzdenkens, Florin Lowndes describes the four aspects of meditative work that George discovered. The first three aspects can be described easily while the fourth level is a state of grace.

First Aspect: The first step in meditating the Philosophy of Freedom is learning to perceive what is on the page. This perception would include the number of paragraphs and the main themes of each paragraph. Making synopses is the fastest way to internalize the content and to test your own retention of the path/order of Steiner’s thoughts. O’Neil recommended making one-sentence synopsis for each paragraph, plus a catchphrase. (Longer paragraphs may require longer synopses) Placing the synopses in an orderly fashion allows the reader to survey the whole and see how the individual paragraphs interrelate. Imagine how the 19 paragraphs of the first chapter would look lined up with their synopses and catchwords. Study groups have a completely different quality when members bring their synopses sharing them with the group, giving and taking feedback. Great process. (Contrast this process to the current practice of a study group leader trying to lecture on the content of the Philosophy of Freedom in front of a passive audience. )

Second Aspect: The second aspect is to find the form of the chapter. George gave his results for the chapters of the Philosophy of Freedom but other (better) versions may be found with time. (This organic form work is still in its infancy so there is much work to do in testing George’s results so that the proper treatment can be given to Steiner’s work.) For chapter one, the form appears as a series of seven-forms consisting of 19 paragraphs. The 19 paragraphs have three waves. By studying and taking notes about the climb and swoop of each wave, about the symmetries and polarities, the group starts to see the organic interconnections of Steiner thought-process.

Each wave moves thematically from outer to inner perspectives like the Goethean archetypal plant. When the group can see all of the symmetries and interconnections of the catchwords on the white board in diagram form, it has attained the stage that George called walking through the garden. If you can close your eyes and still see in your mind’s eye where each idea stands in relation to the others and move through each wave with ease, you are ready for the meditation. It is at this point where you can recall all 19 paragraphs without notes (minimal notes) that you are practicing organic thinking. Here Steiner’s provocation makes sense: “one must become master of the idea, or fall into its servitude.”

This meditation is powerful and opens the chakra of the heart and is the reason Steiner called it “heart thinking.” Is your branch lacking in love, this is a great way to get members to open up. Practicing the O’Neilian way by retelling a whole chapter of the Philosophy of Freedom is similar to an acting class, or ritual of organic thinking. Each chapter is like musical scale that must be experience in body, thought, and feeling. It requires awareness and will forces. Because the group sticks with a chapter for several weeks, new members can be prepared to become anthroposophical group leaders and lecturers who really know the ideas of the text and the new thinking behind each chapter, paragraph, and eventually sentence. The local branch would be a training facility for new thinking, three-folding, and spiritual development, a practice which is widespread in the Theosophical Society but completely absent from the branch and youth group of the Anthroposophical Society. There is no bridge between generations because branch life provides no skill training or mentorship. When George was around things were different.

Third Aspect: The third step according to George and Florin is applying Steiner’s organic forms to everyday life situations. Try to write short notes, essays, or lists according to the levels of the organic thinking.[v] Tell a story in organic form. Plan your lessons for school with a clear build up of what? how? why? Afterall Steiner gave a three-fold lesson plan, and now you can make a New Waldorf lesson plan consisting of a 4-fold, 7-fold, or 2-fold plan if you learn the scales of the new thinking in the Philosophy of Freedom.[vi] The branch meeting agenda could also be organized according to physical, etheric, astral and ego parts of the meeting. This may be a giant leap for most, but O’Neil’s approach leads there quickly. By applying the forms of the Philosophy of Freedom, a new level of mastery is attained.

Fourth Aspect: Meditate the Being behind the chapter’s thought-form. Who knows how to do this?

Conclusion: The Philosophy of Freedom is not simply a philosophy book. It is a book about raising group consciousness from a merely logical thinking to an organic spiritual thinking. Once there is a critical mass of people who have started to think organically via the Philosophy of Freedom, Steiner’s work can pour into the world in the form of will forces and living intuition. The future is in studying together in a way that creates a deep loving bond as well as dynamic thinking patterns so that human beings can work together in life’s great projects.

SYNOPSES OF CHAPTER I, Philosophy of Freedom

Chapter I, Conscious Human Action

1/14 What? Freedom question: Is the man free? Supports and detractors: D. Strauss freedom of choice is empty; Steiner there is a reason why one chose an action.

2/10 How? Freedom opponents: Against freedom of choice: Spencer freedom of choice is negated; Spinoza: necessity of our nature and God’s nature is free necessity.

3/5 Why? Created beings determined: Spinoza: the stone is determined to roll by external cause.

4/6 Who? Spinoza’s definition of freedom: Human know he is striving and therefore thinks he is free: conscious of his desires but not causes: child and milk, knows the better and does the worst.

5/16 Why? Spinoza’s Error: Spinoza has a lack of power of discernment: motive of actions which I understand are not equal to organic process of desiring milk.

6/6 How? Hartmann’s character-disposition: will is determined by circumstances: or mental picture is made into motive based on character disposition. Spinoza’s error.

7/3 What? Additional questions: freedom of the will one-sided? Connected to other questions?

8/3 How? Question of conscious motive: The question of the difference between a conscious and unconscious motive will be next.

9/3 Why? Knowledge of the reasons?: man divided into two parts the doer and the knower, but never the one acting out of knowledge.

10/2 Who? Kant’s definition of freedom: freedom is the dominion of reason, or life according to goals and decisions.

11/3 Why? Kant’s error: is reason determining too? Then freedom is an illusion!

12/2 How? Hamerling’s motive determines volition: man can do what he wills, but he cannot will what he wills, because his volition is determined by motives.

13/6 What? Are motives only compelling? Hamerling does not differentiate between conscious and unconscious motives. No freedom!

14/1 How? How decisions are made: not whether I can carry them out.

15/13 Why? Rational thinking: no animal analogies, and Paul Ree: the stone and the donkey – causality is invisible. Conscious motives?

16/1 Who? No notion of freedom: enough examples.

17/6 Why? Significance of thinking and Hegel: thinking gives man’s actions their unique character.

18/20 How? Actions arise from thinking, MP’s, motives, Gemuet, and love: The more idealistic the mental picture the more blessed is the love.

19/2 What? Final question: essence of human action must be preceded by the question of the origin of thinking.

Mark Riccio, graduated from the Waldorf School in NYC. He studied anthroposophy with Frank Teichmann in Germany and later with Florin Lowndes. He finished his doctorate degree with a dissertation on Waldorf Education. Mark has led many study groups and is always trying to find converts to the Philosophy of Freedom. His most recent book is the Logik of the Heart available on amazon.

[i] To find some of George and Gisela’s mimeographed documents go to: https://www.organicthinking.org/1-background-of-rudolf-steiner-s-organic-thinking/

[ii] The Human Life by George and Gisela O’Neil and Florin Lowndes (Mercury Press, Chestnut Ridge, NY) The book first appeared in serial form in the Anthroposophical Newsletter. It has been translated into over ten languages.

[iii] The Philosophy of Freedom by Rudolf Steiner. There are many translations available online. For the purpose of studying the organic thinking, it is necessary to correct an existing translation by checking it against a pre-1925 German original edition. Lindeman’s translation, The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity is the closest to the German in terms of paragraph- and sentence-structure and thus requires the least fixing. My translation called The Philosophy of Freehood should be available early 2020 with properly numbered paragraphs and colored sentences. Check my website for further details: www.organicthinking.org

[iv] Die Belebung des Herzchakra, The Human Life, and Das Erwecken des Herzdenkens were all published by Freies Geisteslebens Press, the main anthroposophical press in Germany. These books marked the recognition of George O’Neil’s approach and the rediscovery of Steiner’s method. A book review by Ralf Gleide said this much in DIE DREI (Heft 11, 1998).

In the 1990s Lowndes’ seminars were sold out and his books and articles created quite a stir. He singlehandedly brought new life into the six exercises with his book and seminars. And his seminars on Steiner’s new thinking caused many, even in old age, to reconsider how they were reading the Philosophy of Freedom.

A meeting was held in Orbey, France at Maison Oberlin where 36 anthroposophical doctors, CC priests, AYS youth, and Florin Lowndes gathered to found the Society for Organic Living Thinking (GOLD in German). This meeting was the official rebirth of Steiner’s new thinking. We are currently founding The George O’Neil Group foundation here in the U.S. to support honest translations, seminars, and eventually a college of new thinking.

[v] The Logik of the Heart: The organic templates of spiritual writers, Rudolf Steiner, and The Philosophy of Freehood covers many aspects of O’Neil and Lowndes’s work. It also includes a section on other authors who organized their books in a similar fashion as Steiner, thus showing that this method of organic thinking is universal.

[vi] An Outline for a Renewal of Waldorf Education by Mark Riccio (available at Waldorfbooks.com) realigns Waldorf’s mission to Steiner’s original intention as a new thinking school for spiritually oriented children. New teachers need a new thinking and time is running out.